By Julianne Hughes, TBS Teaching Artist

Art making is an important part of a child’s education because it encourages students to make connections to other disciplines like history, science, math, and language in a way that for can enhance their comprehension. Students practice the processes of learning through artmaking — making mistakes, changing course, problem solving, making a plan, and seeing a project through.

Some people believe artistic ability is gifted to some and not others. I don’t believe that at all. Each of us has the capacity to create as a means to express ourselves. As an art educator, I get the opportunity to observe which art skills come easiest for each student, whether it’s writing, building, drawing, storytelling, then guide and support them to understand the art language that they are uniquely equipped to express to others. By experimenting with materials, music, movement, and drama, students develop their art languages and use those to express themselves or an idea.

What does success in the art studio look like? Being open to trying new materials translates to success in the art studio, having things fail spectacularly and continuing to completion is what success can look like in the art studio.

Getting back to the idea of art as a language and as a form of expression, often times artists don’t know what they’re expressing until they look at it later. Process artists start with an idea of a process and materials, and find their way through to arrive at a product. Conceptual artists start with an idea of a finished product, then determine the materials and processes to achieve their vision. Students can be, and are often both!

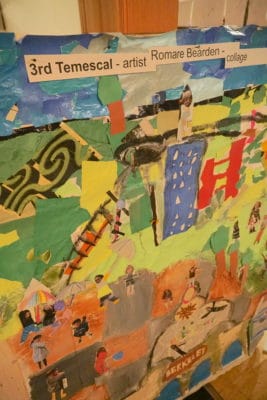

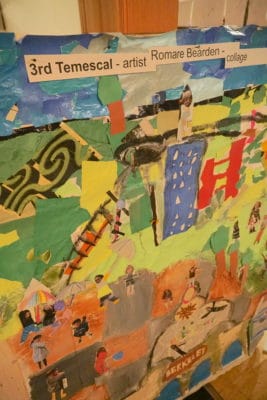

Here at The Berkeley School, we’re constantly referencing the work of other artists, past and present, to inspire our own artmaking. One artist we’ve studied recently is Romare Bearden, an artist who came to prominence during the Harlem Renaissance. Romare Bearden used the materials around him to make art. He would collect paper ephemera (newspapers, posters, magazines) and create layered art pieces that authentically portrayed the essence and culture of his Harlem neighborhood. His work disrupted the narrative of the time about the African-American community and told a story that was not being told. Inspired by his work, TBS 3rd graders created a map of our University Avenue community using a layering style similar to Romare Bearden’s in order to emphasize the “layers” behind the history of our own neighborhood. The resulting piece gave acknowledgement to the indigenous Ohlone land that our school was built on, and harkened back to the fact that our historic building served as a train station at the start of the 20th century.

Art as civic engagement is not a new thing. Artists have always been at the forefront of supporting civic engagement.

Contemporary artist Alma Woodsey Thomas was an art educator for 40 years before she became known for her expressionist paintings. It was in her retirement that she was recognized with a show at the Whitney Museum in New York. she was the very first African-American woman to have a solo show at the Whitney in fact. During her youth, Alma was not even allowed into the Whitney Museum, since it restricted access to African-Americans. For Alma, giving her students another language to express themselves was her purpose as an educator. I feel a similar purpose in my role as one of The Berkeley School’s teaching artist. I hope to impart in my students the understanding that materials and processes can serve as modes of communication and expression. Materials — such as clay, metal, and fabric — respond in different ways during artmaking processes: what an artists does with or to those materials can inform the viewer of what it is the artist is trying to say.

Mildred Howard, a Berkeley-born interdisciplinary artist, recently inspired a project our kindergarteners took on in the Art Studio. Students used sticks and tape to create small house shapes that would all be used to complete one collaborative art piece conveying the importance of neighborhood. The magic of this lesson was showing very young artists that they can be a part of something big. Not only did the artmaking process help them learn how to share materials and make space for one another, it allowed them to learn to normalize conflict and practice stepping up and stepping back.

Mildred Howard, a Berkeley-born interdisciplinary artist, recently inspired a project our kindergarteners took on in the Art Studio. Students used sticks and tape to create small house shapes that would all be used to complete one collaborative art piece conveying the importance of neighborhood. The magic of this lesson was showing very young artists that they can be a part of something big. Not only did the artmaking process help them learn how to share materials and make space for one another, it allowed them to learn to normalize conflict and practice stepping up and stepping back.

In the TBS art studio we ask how looking from another perspective can help us understand ourselves and others. Our throughline is “How does art invite us to engage with our community?” and “How can art facilitate change for the better? These are questions I ask myself not just as an educator but also as an artist myself.

This year, I represented The Berkeley School as one of 400 partner delegates to attend the

For Freedoms Congress in Los Angeles, a convening of artists and arts institutions to ideate pathways for civic participation through art in the lead-up to the 2020 elections and beyond.

Artists from across the country and from of all different levels of renown gathered in Los Angeles over a period of four days to present ideas, learn from each other, and work together to formulate ways promote civic engagement in our home communities through art.

Founded in 2016 by artists Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman, For Freedoms is a platform for creative civic engagement. Inspired by Norman Rockwell’s paintings of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms (1941)—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—these public exhibitions and installations spark discussions on civic issues and core values, and advocate for dialogue and civic participation.

At the core heart of the “For Freedoms” movement is the role of the artist as the poser of this important question: “How can artists and other storytellers and creative people come together to move beyond division and uplift humankind?” In 2018 For Freedoms launched a nationwide public installation project — the largest group effort in history — to bring together artists from all 50 states to install projects that spark a national dialogue about art, education, commerce, and politics. The Berkeley School participated in that nationwide activation with a project of their own called “Lawn Sign Activation: What’s important to me”. Our 4th & 5th grade students designed lawn signs to post along the road adjacent to our school to communicate the issues that matter to us and inspire others to think about issues that matter to them.

Mildred Howard, a Berkeley-born interdisciplinary artist, recently inspired a project our kindergarteners took on in the Art Studio. Students used sticks and tape to create small house shapes that would all be used to complete one collaborative art piece conveying the importance of neighborhood. The magic of this lesson was showing very young artists that they can be a part of something big. Not only did the artmaking process help them learn how to share materials and make space for one another, it allowed them to learn to normalize conflict and practice stepping up and stepping back.

Mildred Howard, a Berkeley-born interdisciplinary artist, recently inspired a project our kindergarteners took on in the Art Studio. Students used sticks and tape to create small house shapes that would all be used to complete one collaborative art piece conveying the importance of neighborhood. The magic of this lesson was showing very young artists that they can be a part of something big. Not only did the artmaking process help them learn how to share materials and make space for one another, it allowed them to learn to normalize conflict and practice stepping up and stepping back.